· Richard Webber · Articles · 12 min read

Diversity among the Olympic Teams

“Multi-culturalism” is a key value of the Olympic movement.

Background

“Multi-culturalism” is a key value of the Olympic movement. London’s bid for the 2012 Olympics relied strongly on the positioning of London’s strongly multi-cultural character as a global city with communities from every country in the world. The favourable coverage of the Games in the British Press focused on the positive attitudes of the crowds towards competitors of every cultural background.

One of the two “faces” of Team GB was of mixed race and its most successful competitor arrived in Britain as an eight year old from Somalia.

But how diverse was Team GB? And how did its level of diversity compare with that of teams from other countries which have acquired large communities of economic migrants since 1945? And to what extent do the sports disciplines of competitors from migrant communities differ from those from the host communities within which they live? The purpose of this paper is to answer these questions using the names of the 10,881 athletes who competed in the games.

Inferring cultural background from names

Research into the behavioural differences of people from different cultural backgrounds usually relies on them assigning themselves to an ethnic, religious or cultural category contained in a list. Such categorisation clearly has its purposes. However it also has its limitations. There are many contexts in which it is inappropriate even if possible to ask an individual what category he or she belongs to; when asked many people not unreasonably decline to answer; in many contexts, as for example when competing as part of a national team at the Olympics, the accurate answer, in so far as there is one, is often inappropriate for the particular object of the analysis; besides many second, third or further generation immigrants have allegiances both to their nation of birth and to the culture of their parents or grand-parents, which one being the foremost at any particular time depending on context and occasion.

It is for these reasons that there are circumstances where analysis of population groups by their personal and family names is more likely to contribute insight into cultural differences. The ethnic composition of the teams competing at the London Olympics is a good example of such an occasion as the results of the following analyses may show.

The file of competitors

The findings which follow are based on an analysis of a data file containing the names of the 10,881 individuals who competed in the 2012 London Olympics. Other than for some Brazilians the data file contains personal and family name, team and sporting discipline. The file does not give result. Nor does it contain information on competitors in the Paralympics.

Where a competitor entered for two or more events, whether in the same or different sports, only one record is retained. Where the competitor entered for different sports, he or she was coded by the name of the sport coming earliest in alphabetic order.

The coding

Using both elements of their name the 10,881 competitors were coded into one of 200 or so Origins categories, these being territorial groupings of people sharing a common disposition towards the use of particular personal or family names. As would be expected these categories, though not based on nationality, overlap closely with national groupings. Sometimes they are more detailed, such as Basque, sometimes less detailed, such as Spanish speaking South America, than classifications based on nation states.

These detailed categories are typically grouped into broader religious and cultural groupings, such as “Black Africa”, “The Muslim Word” or “Hispanic”.

The classification of names is made possible by the use of tables created from analysis of some one billion people’s name, associating some two million family names and some 700 thousand personal names with one or more Origins categories. Where the coding of the two elements of a person’s name clash, a set of rules are used to arbitrate so that each named individual is assigned to a single Origins classification.

The file of competitors at an Olympic Games is as culturally diverse a list of names as one is ever likely to be able to source. In the case of the 10,881 competitors in London 2012, 98.9 % were able to be matched on the basis of either personal or family names and thereby accorded an Origins classification.

Findings

A : Diversity among teams from “advanced” western countries.

One potentially interesting use for the information is to examine the extent to which different “advanced” western countries have been successful in including members of minority ethnic groups, in particular recent immigrants, in their national teams.

To throw light on this we have extracted the names of competitors from a set of 18 teams, these being from those countries of Europe west of the former “iron curtain” (but not Austria), the United States and Canada, Australia and New Zealand. These, generally speaking, are the most popular destination for long term economic migrants.

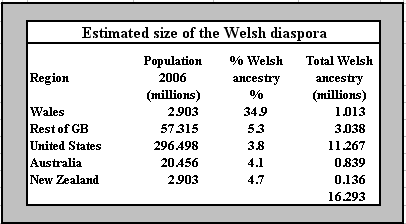

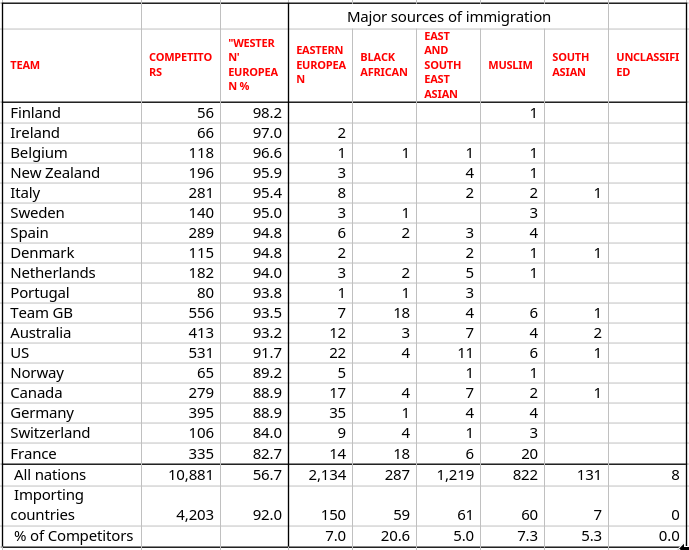

Table one shows the proportion of athletes in each team with what can be classified as Western European names together with the number with names from five principal areas of immigration, Eastern Europe (countries formerly part of the Soviet bloc), Black Africa, the MuslimWorld, East and South East Asia and South Asia. Eight athletes from the 18 teams had names which could not be assigned to any Origins code.

The 18 teams have then been ordered in descending order according to the proportion of their competitors who bear “Western European” names.

Table 1 : Representation of competitors from “Western” teams according to the Origin of competitors’ names

The most immediately telling implication of these statistics is that it is the French rather than Team GB that contains the largest proportion of people with non-Western names, somewhat of an irony given London’s positioning against Paris as the more “inclusive” city in which to hold the games.

17.3% of the French team’s members have non-Western names, nearly three times the 6.5% achieved by Team GB whose rate is marginally lower than the 8.0 % average for this bloc of countries.

This statistic is also ironic when considered in relation to the current British press coverage of civil disturbances in Amiens and elsewhere from which it is inferred that France has been particularly ineffective in integrating minority populations when compared to other European countries.

Though the French team constituted less than 8% of the competitors from “western” countries, it contained over 30% of their Black African athletes and over 30% of the athletes with Muslim names representing a “western” nation.

Whilst Team GB had as large a Black African contingent as France, albeit from a much larger team, Britain has been much less effective than France in developing sporting excellence among the Muslim community.

In all fairness the table ignores the contribution made by Britain’s communities of West Indian origin, most of whom have British names. However today this community represents less than 10% of Britain’s minority population as well arguably its most socially integrated one.

A second interesting implication of the table is that 45% of all “non-western” competitors from “Western” teams bear names from Eastern European. This figure is hugely in excess of the proportion of this set of communities in the western European population. The contribution of eastern Europeans to Germany’s team is eight times that of Germany’s population of Muslim origin. The group is also significant in the United States and Canada, in Australia and in Italy.

Given the prominence of Eastern European countries in medals tables over past Olympiads, this may reflect the high status accorded to sports in Eastern European cultures and, who knows, even genetic differences. It may challenge the assumption that current success in sport in Eastern Europe is determined by economic considerations or the importance attached to it by former regimes.

A third interesting finding from the table is the disproportionate number of Black African athletes in the London Olympics who represent “western” teams. Among the other major name groups, ie Eastern Europeans, people from the Muslim world, South Asians and South East and East Asians, around 5% represent “western” countries. The comparative figure for Black Africans is 20%. It is difficult to believe this reflects differences in the relative size of the indigenous and emigrant communities. Rather, as used to be but is no longer the case with West Indians, it more likely reflects differences between Black Africa and the west in terms of opportunities to train and complete.

We have explained above that there are instances when Origins codes are more detailed that national categories. Examining the names of Olympic competitors allows us to see the important contribution that the Irish, Scots and Welsh make to the teams not just from Britain and Ireland but also from North America and the Antipodes. As many as a third of the New Zealand team and just under a quarter of the Australian team owe their names to Celtic ancestry. These figures are particularly interesting when compared with the distribution of these countries’ population. The distinctiveness of the Celtic diaspora is also evident from the profile of sports in which they tend to compete.

| TEAM | COMPETITORS | ANGLO-SAXON | CELTIC | CELTIC AS % OF BRITISH ISLES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team GB | 556 | 346 | 132 | 27.6 |

| Australia | 413 | 222 | 97 | 30.4 |

| US | 531 | 255 | 77 | 23.2 |

| New Zealand | 196 | 96 | 64 | 40.0 |

| Canada | 279 | 107 | 49 | 31.4 |

| Ireland | 66 | 12 | 46 | 79.3 |

Table 2 : Contribution of competitors with Celtic names to various national teams

B : Cultural preferences

There is no contesting the evidence that different national teams have different strengths and weaknesses. The Chinese dominate table tennis, the South East Asians excel at badminton, the Latin Americans succeed at football, competitors from Scandinavia and the Baltic States are disproportionately found in athletic events that involve throwing. Jamaicans run fast and East African run fast further.

There is no shortage of debate and analysis on how far these differences are cultural and how far genetic.

The file of competitors allows us to contribute to this debate by examining how the profile of sports engaged in by immigrants compares with the event profile of host population.

Taking just competitors belonging to the teams listed in table 2 we can examine the relationship between competitors’ cultural origin based on their name and the sports in which they competed.

Here are some of the most interesting findings:

- Competitors of Celtic origin constitute 22.8% of competitors from these countries. Relative to other members of the teams they are the most likely to compete in the Modern Pentathlon (46.2%), Canoe Sprint (35.7%) and Triathlon (33.3%). They are also over-represented at Judo and Equestrianism.

- By contrast no competitor of Celtic origin competed in Archery and only 6 of those who shot had Celtic names. Synchronised swimming is another sport which fails to appeal to the Celtic diaspora wherever they have settled.

- Though Eastern Europeans make up just 3% of these squads, they account for a quarter of the competitors in tennis.

- Rowing is a popular choice of sport with both Eastern and Southern Europeans, with less than 5% of the squads accounting for more than 10% of the competitors in these sports.

- Though fewer than 1% of the squads compete at table tennis, a half of squad members with East and South East Asian names are table tennis players.

- Hispanics box.

- Competitors with Black African names gravitate not just to athletics but also to basketball and volleyball.

Conclusions

From this limited set of analysis of the competitors at the London 2012 Olympics it is possible to draw a number of conclusions.

The first of these is that name, however imprecise its accuracy may appear, is nevertheless a highly predictive discriminator of country of origin and often of quite subtle differences in behaviour.

Contrary to assumptions among the British media, there is little evidence to suggest that there has been any greater success in Britain in involving minority groups in sport than there has been in other countries with large numbers of economic migrants. If the contribution of minority groups to national teams is to be taken as a reliable indicator of the effectiveness of multi-cultural policies, then it would seem that France has been the most effective western nation in this respect, notwithstanding the adverse impressions given by the British media’s coverage of recent events.

France is in a unique position among western nations in having harnessed talent from the Muslim community. This contrasts with the situation in Germany, the multi-cultural nature of whose Olympic team is based on the involvement of Eastern Europeans rather than Germany’s large Turkish community as indeed is the case in German football and German tennis.

Both Australia and New Zealand, which pride themselves on the size of the minority ethnic groups, have found it relatively difficult to find competitors of Olympic standard from members of minority groups.

The experience of Germany in particular, and of other “western” nations in general, is that people of Eastern European origin constitute the largest potential group for generating competitors of Olympic standard. It is not evident that this target group has been recognised for its potential in Britain or indeed that it is recognised as a particularly important element in the country’s multi-cultural character.

The association of particular groups with particular sports, rather than with sport in general, persists after emigration and, on the basis of evidence of people with Celtic names, for multiple generations of immigrants. This supports the contention that genetic predisposition towards particular sports may be much more nuanced that the simplistic “white-black” differentiation, particularly in relation to capability at running.

Within the white populations differences do appear to cluster in relation to persistence and versatility, as with the triathlon, and in relation to ball sense, a skill which according to geographic region may manifest itself in tennis, football or water polo.

On the other hand the persistence of interest in table tennis among immigrants to the United States from East Asia supports the contention that sporting preferences persist notwithstanding social and economic change.

Almost without exception the findings of these provisional analyses provide support to “urban myths” and challenge the assertions promoted by media and political elites.