· Richard Webber · Articles · 4 min read

Social cohesion

An evidence base for tackling social cohesion

A few years ago a communications team from the Slough PCT identified a problem with Sikhs. Very few of them were presenting at a screening service for checking early stages of diabetes. Slough has one of the largest Sikh communities in Britain so a campaign was launched. After early failures a communications centre was set up in the car park of a large Sainsbury’s supermarket, but to no avail. It was explained to the team that shame would accrue to Sikh men who were found to be diabetic and that the only way to overcome this shame would be for the elders of the community to join the campaign in support of the screening centre.

This is just one of many examples of the effectiveness of community leaders in facilitating public campaigns. Building links with such leaders is now a critical task of police forces, health authorities, social services teams, planners, housing departments and electoral registration officers. In a place such as Slough such links are effective because Sikhs are a large and coherent community in the town.

But what of Wood Green or Walthamstow? Here you find a melting pot of different communities, all living cheek by jowl, members of a diaspora in some circumstances but seldom reachable through local leaders. If you live in Wood Green you are obliged to speak English since no individual minority is large enough to dominant the community. Everyone must get along with members of other communities, to communicate English and to adjust to life in a melting pot without the security of existing in a parallel universe.

The experience of Jasvinder Sanghera, CBE, born to a Sikh family in a suburb of Derby, highlights the oppression that can occur in a mono-cultural community. The “victim” of a forced marriage at the age of fourteen and unable to escape honour based abuse, her book “Shame” highlights the oppression of living in a community which offered no opportunity to challenge its views.

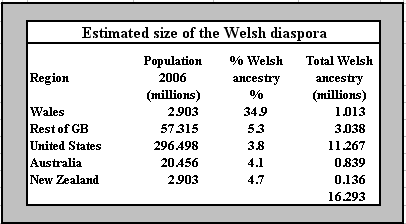

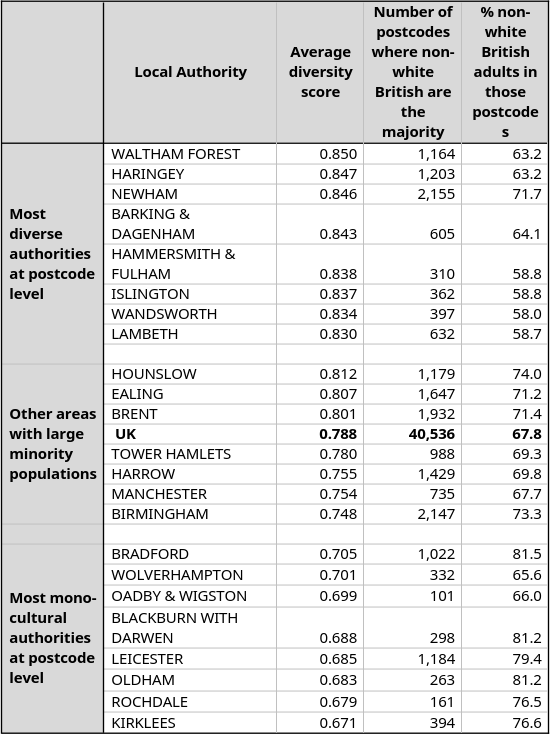

To help local authorities map out the different strategies they may need to adopt to tackle social cohesion Big Data has been used to identify the level of diversity in 2016 in every street in Britain. Using the names of 50 million adults, analysed at the level of the unit postcode (eg N6 6DJ) an algorithm predicts the probability with which and two adults, taken at random from the postcode, will belong a different one out of 40 minority communities. A high score on this measure occurs in places such as Wood Green where streets contain members of many different minorities. Low scores occur in ethnic minority areas dominated by a single ethnic minority group.

The eight local authorities whose streets, on average, are the most diverse and where it is therefore most difficult to identify minority community leaders are all in London. The ten where streets tend to be dominated by a single (non-white British) minority are in the Midlands and either side of the Pennines. Life as a member of the minority population is very different depending on which one you live in.

Clearly in the London group there are serious risks of inter-communal tensions but little evidence of conflict with the host community, which is largely absent. At the opposite end of the scale are communities which tend to operate in a parallel universe, which have strong internal links, but poor connectivity with outsiders.

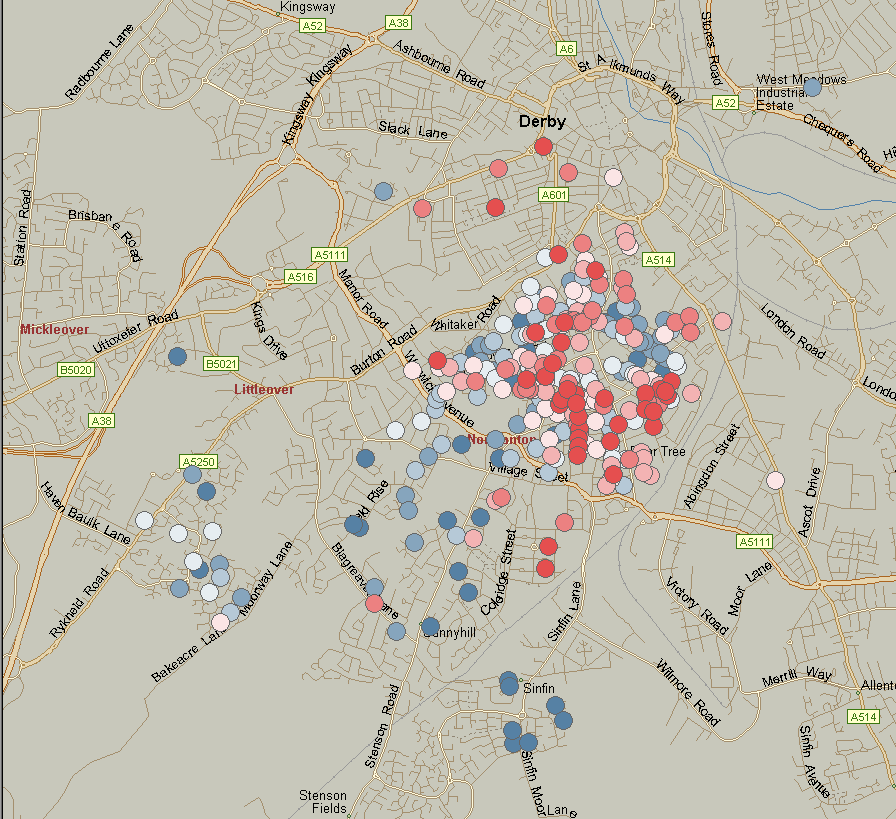

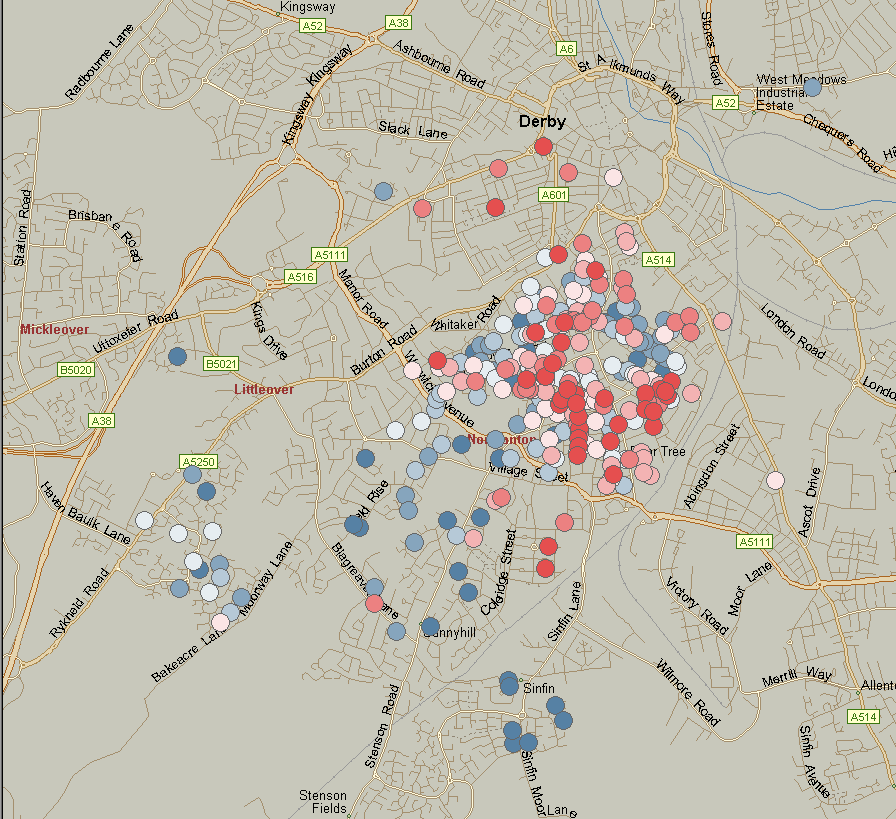

Figure one: social cohesion in Derby

Figure one: social cohesion in Derby  Table one: local authorities with high and low levels of diversity at postcode level

Table one: local authorities with high and low levels of diversity at postcode levelWhat patterns emerge?

Derby, where Jasvinder Sanghera lived, is typical of many authorities which contain a mixture of mono-cultural and melting pot streets. As in other cities the older-established inner city in which immigrants first settled are the most diverse. It is the more suburban locations to which immigrants have more recently where community leaders are easier to location but where problems such as those experienced by Jasvinder are most likely to be hidden. Contrary to what had been assumed, the more prosperous members of minority communities are tending not to move to live in white neighbourhoods but to move to communities which are physically separated from members of other minority communities.

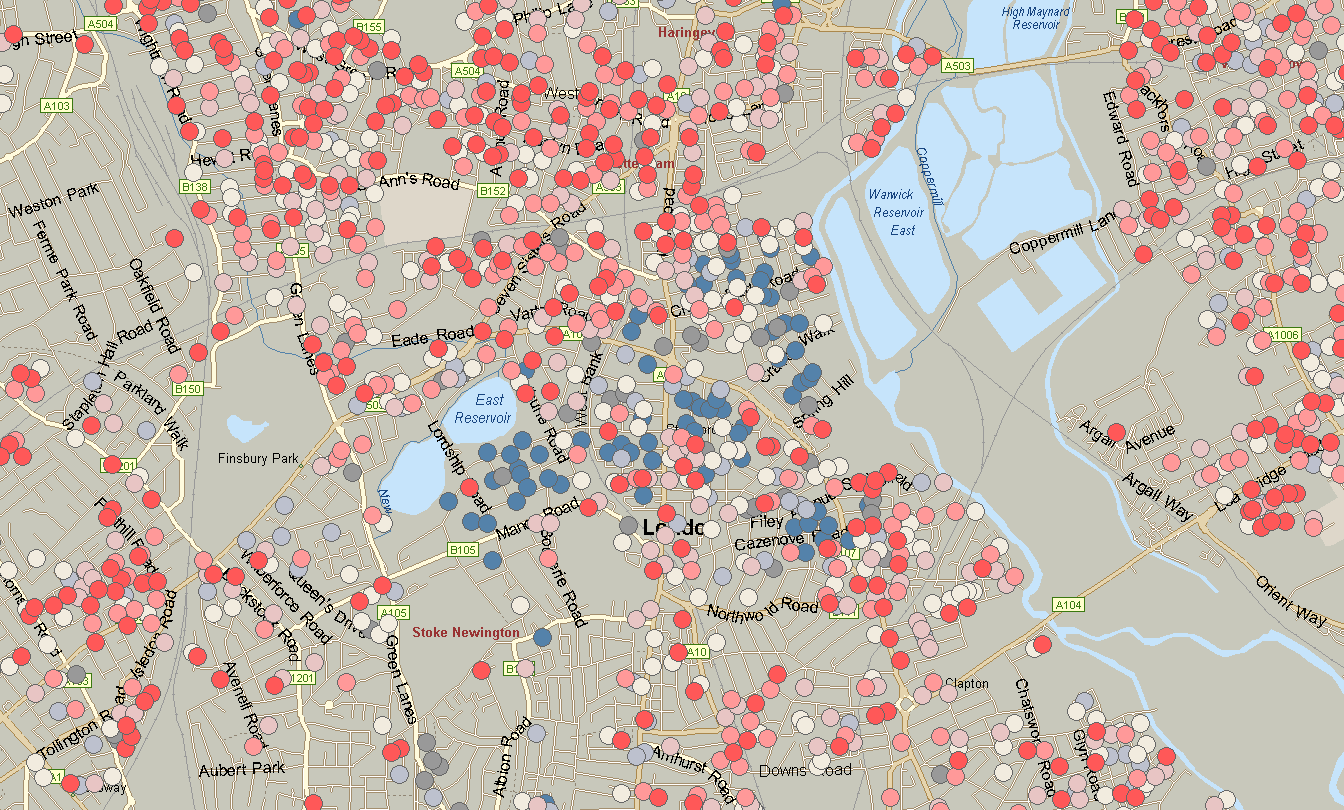

Figure 2 :Cohesion around Stamford Hill in North London

Figure 2 :Cohesion around Stamford Hill in North London